Anti-Semitism

by Ben Macri, Vassar '99

In the cultural climate of nineteenth century America anti-Semitism was an acceptable form of social prejudice. There has been a history of anti-Semitism in western society for centuries, and the United States is no exception to that fact. The political uses of anti-Semitism had been well proven before, and would be proven again in the 1896 presidential campaign. No political party was above using anti-Semitism, especially to appeal to Christian constituents, but it was the Populist party who used anti-Semitism most distinctively.

Since the origins of the Populist movement, anti-Semitism had found its way into Populist doctrine. Many important Populist thinkers considered Jews to be at the root of problems for the farmers who made up the Populist party's rank and file. Of course not all Populists were anti-Semitic, and some even attacked the party for its prejudice, but anti-Semitism was definitely a theme in Populist ideology. Jews were an easy villain for the Populists to use, since the party was dominated by rural farmers and other small businessmen, people from areas of the US where there were few Jews. It was easy for the Populists to suggest that it was these unseen Jews who were responsible for farmers' financial difficulties. Since many of the Populist party's rank and file had never seen a Jew they only had stereotypes of Jews to base their opinions on. It was an easy jump from those stereotypes to a political platform with anti-Semitic tendencies. It was easy to blame local financial problems on large, unseen groups.

Anti-Semitism was not something which was confined to the early history of the movement, or to its rank and file. William Jennings Bryan was adept at switching between coded anti-Semitic language, and preaching people's need to get past racial prejudice. The most notable example of Populist anti-Semitism can be found in the novel A Tale of Two Nations, written by the Populist thinker "Coin" Harvey, who was also the author of Coin's Financial School, one of the most popular pro-silver arguments to be published during the Populist period. A Tale of Two Nations was the story of a wealthy London banker, Baron Rothe, who engineers a plot to keep the United States from ever using a silver as currency. In the novel Rothe sends a henchman to the US to `encourage' congressmen and economists to support the gold standard. The henchman, Rogasner, falls in love with an American girl, who is in love with a Nebraskan congressman of the pro-silver variety. The characters in the book are either thinly disguised historical figures or thinly disguised racial stereotypes. Rogasner, the dark European was clearly a Jewish villain out to ruin the Caucasian race. His love was a shixa goddess, protecting herself from the threat of miscegenation by falling in love with the literary equivalent of William Jennings Bryan. And the Rothe character was a symbol for the Rothschild House. All of this fit neatly into Harvey's Populist theory of history which saw the Jewish banking houses, and therefore the Jewish race, as the source of the common man's problems.

Populist anti-Semitism worked its way into the 1896 campaign through the Morgan Bonds scandal. When the public learned that President Cleveland had sold bonds to a syndicate which included JP Morgan and the Rothschilds house, bonds which that syndicate was now selling for a profit, the Populists used it as an opportunity to uphold their view of history, and prove to the nation that Washington and Wall Street were in the hands of the international Jewish banking houses. The currency issue itself was loaded with anti-Semitism as the Populist returned again and again to crucifixion metaphors to argue against the gold standard. The reference was clear. The same Jews who were responsible for the death of Jesus were responsible for the currency crisis. The message was clear to the many Protestants who filled the ranks of the Populists.

Cartoons on this Site with Antisemitic References

April 15, Sound Money

June 21, Denver New Road

August 6, Sound Money

August 20, Sound Money

October 15, Sound Money

October 22, Sound Money

November 5, Sound Money

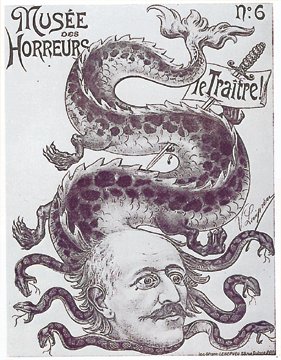

A poster depicting Alfred Dreyfus as a snake. In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus--the only Jewish member of the French general staff--was accused and convicted of spying for Germany. He was exonerated of all charges a decade later, but only after strenuous protests on his behalf. The case was widely followed in the U.S.

Observing the Dreyfus Affair, Theodor Herzl, a Jewish journalist in Austria, concluded that Jews would never be equal citizens in Europe. In 1896 he published A Modern Solution to the Jewish Question, one of the first modern works advocating a Jewish state.

This image is from the site Beyond the Pale: The Dreyfus Affair.

"Even more significant, Populists strengthened their cause by using religious metaphors to link money with a Jewish conspiracy. Thus, in 1896, Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, speaking in an idiom Protestant Fundamentalists were fully conversant with, could easily intersperse biblical imagery with economic necessity when he thundered, `You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.' The antisemitism evoked by the metaphor of the crucifixion was powerful and appealed to rural Protestants who possessed a similar religious and cultural heritage with other Americans in the South and the West." --Leonard Dinnerstein, from Antisemitism in America (p.49-50).

"We are not attacking a race, we are attacking greed and avarice, which know neither race nor religion. I do not know of any class of our people who, by reason of their history, can better sympathize with the struggling masses in this campaign than can the Hebrew race." --William Jennings Bryan, in a speech to a Jewish audience, from The First Battle (p.581).

"Redemption money and interest-bearing bonds are the curse of civilization. We are paying tribute to the Rothchilds of England, who are but the agent of the Jews." --Mary Elizabeth Lease, a Populist speaker, as reported by The New York Times on August 11, 1896.

"While the jocose and rather heavy-handed anti-Semitism that can be found in Henry Adams letters of the 1890's shows that this prejudice existed outside Populist literature, it was chiefly Populist writers who expressed that identification of the Jew with the usurer and the `international gold ring' which was the central theme of American anti-Semitism of the age. The omnipresent symbol of Shylock can hardly be taken in itself as evidence of anti-Semitism but the frequent references to the House of Rothschild make it clear that for many silverites the Jew was an organic part of the conspiracy theory of history." --Richard Hofstadter, from the article "The Folklore of Populism" in Antisemitism in the United States (p.61).

"There is no doubt that in their intense hatred for the 'money power,' some Populists accepted anti-Semitic stereotypes and identified Jews with the evils of society. [...] There is doubt, however, that the Populists did this any more frequently than other groups in society." --Louise A. Mayo, from The Ambivalent Image: Nineteenth-Century America's Perception of the Jew. (p.131).

"Despite the suggestions of some writers, this reasoning need not be taken to indicate that these advocates of silver were any more tainted with anti-Semitism than any other group in American society. During the 1890's the entire Western world accepted certain stereotypes of the Jew, which were in no way peculiar to the Populists, Bryanites, or any other advocates of free silver." --J. Rogers Hollingsworth, from The Whirligig of Politics (p.97).

SOURCES

Dinnerstein, Leonard. Antisemitism in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Hofstadter, Richard. "The Folklore of Populism." In Antisemitism in the United States, ed. by Leonard Dinnerstein. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1971.

Mayo, Louise A. The Ambivalent Image: Nineteenth-Century America's Perception of the Jew. London: Associated University Press, 1988.