By Sara Lehrhoff, Vassar '99

For more Vassar history, see the website created by Vassar historian Elizabeth Daniels.

In 1896 Vassar College had been open to young women from more than thirty years. Six hundred women from all over the country attended Vassar. Though the school was predominantly Republican, most from north-eastern homes, growing number of students from diverse regions of the country ensured that the Silverites and Gold Democrats were also represented. Suffrage activism was not allowed at Vassar at that time, but the Vassar women still managed to voice their opinions. Rather than protesting, and discussing women's rights, the women took action in a way that was approved by the Vassar administration.

The students, along with various professors, set up a mock election. Each candidate was played by a student. The campaigns were competitive and enthusiastic. The women participated in parades, rallies, and debates, in order to gain support for their candidates. One poster hung during the election proclaimed: "Are you a Republican? Do you want a full purse after Nov. 3? Come to the Republican Rally tonight! Hear speaker Reed, Ex-pres. Harrison, Senator Allison, Senator Sherman, and Mark Hanna. Campaign songs and speeches and a rousing meeting--in the lecture room at eight o'clock! Overflow meetings provided for!" (Claftin, 10/11/96)

Women were voting at Vassar! Women were discussing politics and debating tariffs. Why did Vassar's administration allow this to go on when they were vehemently against suffrage? The answer had to do with political and social attitudes of the time towards women. The Vassar administrators, as well as those outside of Vassar, believed, as the New York Times did, that "the Students follow the campaign as a matter of education" (New York Times, 10/20/96). The young women were learning about politics and culture, and because of this becoming more socially aware. The Vassar Miscellany believed in that same doctrine. "The mock campaign in college, if it has done nothing else, has at least led to a more general reading of the newspapers and brought girls who ordinarily are absorbed in the little round of college affairs to take and interest in the big doings of the outside world" (Vassar Miscellany, 11/96). These young women were not acting as men, but fulfilling the duties of a proper female.

During this period there was an explosion of education around the country. Between the 1820's and the 1890's all seven of the Seven Sister colleges opened their doors. By 1870, the United States Commissioner of Education estimated that approximately 11,000 women were attending seminaries and colleges. Yet with all of these institutions opening feminism was a great fear for most of the new colleges, Vassar included. Because of this Matthew Vassar wanted to ensure that his young women were well rounded students who studied not only academics, but art, music, and physical education.

The opening of these many institution came in conjunction with the changing roles of women in the late nineteenth century. Though there was still an emphasis on marriage, women began to have new roles as "shapers of public sentiment." These jobs included teaching and reform work. Women became the moral reformers of the day. Issues such as temperance became central to many women's lives. But in order to fulfill these new roles women had to be aware of the world around them. It was here that women's institutions such as Vassar became so important. Their job was to not only educate the women in English and Latin, but also politics. The mock election that took place at Vassar was just another form of education in which the women were able to further their knowledge pertaining to issues of the day.

Though Vassar College believed in this doctrine, the administrators and the students did not always view situations in the same way. While the administrators saw the election as an educational experience, the young women may have seen it as something more. Over time "Vassar students began to see themselves as separate from college authorities... They created a student culture with it's own codes of behavior, it's own hierarchy... Vassar authorities had little power to curb autonomous student life." (Horowitz, p. 64 & 68). It is here where the election fit in.

The election as Vassar was almost entirely student run. Representatives from the student body were picked to play the roles of the many politicians involved. Beginning in early October, and continuing right up to the election, the campaign was the main social event of the weekends. On the weekend of October 17th the Republicans held a demonstration. In her letters to her relatives Adelaide Claftin, class of 1897, told of this event:

"Mr. McKinley received four delegations at his home. That is, we had a girl dressed up as Mr. McKinley, another as his wife, and a corner of the Lecture Room fixed up as the porch of his house.... Of course the Lecture Room was crowded, so we had to have police to clear a path for the delegations. There were two delegations of working men, who were dressed up in old coats, overalls, old straw hats, etc. and they carried implements such as the hods that bricklayers use for carrying bricks, etc. -- where they managed to get them I do no know. The head of each delegation made a short speech to Mr. McKinley, and then he replied, and afterwards invited them to shake hands with him and his wife."

Each political party held similar events. The Silverites held a banquet for all of their supporters. Food such as "McKinley on the half shell" and "Squashed Republican hopes"

was served. Friendly competition between the candidates prevailed. On October 26, the delegates held a non-traditional "race to the White House." Adelaide's letters concerning the race read: "Yesterday afternoon we had a bicycle parade by Republicans, and afterward a race on bicycles, by two girls representing McKinley and Bryan. They rode from the lodge up to the front door, where Uncle Sam stood on a bench holding a paper representation of the White House. Of course McKinley beat, and seized the White House from Uncle Sam's hands."

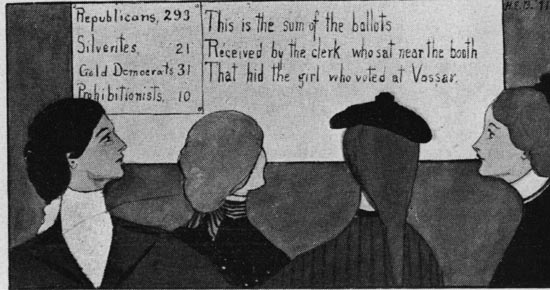

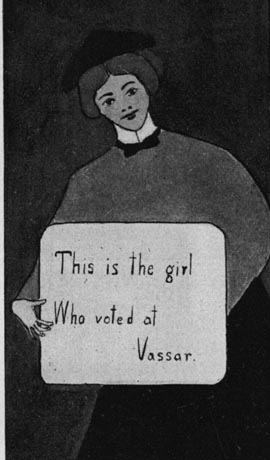

From the 1897 Vassarion

From the 1897 Vassarion

Though the competition was fun and friendly the young women did get to the heart of many issues. The weekend before the election each party held their final rally. At the Republican rally not only were songs sung and cheers cried, but the important topics that the real candidates were covering in their platform were discussed. The student playing M. Wanamaker gave a scholarly discussion about currency, and the unequal value of silver. "Suppose that one of you wanted to give $50,000 to Vassar College. You sit down and draw up a check for the amount, when you have nothing but a salary of $20 a month. Your check is not, of course, honored at the bank. And something like this will happen if we vote for free coinage of silver." (Poughkeepsie Eagle, 11/2/96).

The women were not merely playing a role when they sang their songs and gave their speeches. These women believed in what they were saying. Participation in the mock election was not merely educating them on social and political issues, but giving them a taste of what men are able to do, and what women are not. The students registered to vote, campaigned, rallied, sang songs, gave speeches, and voted. Adelaide described the overall feeling of the election. "Everybody was so enthusiastic and entered so much into the spirit of things that we had a very jolly time,--lots of singing and yelling."

What the administration of Vassar believed to be education was in reality so much more. These young women gained a voice, through the newspapers coverage of their election, and came to realize what it was like to have the power of the vote. The end results of the Vassar election gave McKinley the presidency, with two-thirds of the students voting Republican. The students were able to see the results of their weeks of hard work.

The mock election of 1896 served as not only a voice for the many girls unable to speak on the suffrage issue, but also as a catalyst for many others. They came to see that voting was not something that only men had the ability to do. Women had the initiative, the desire, and the ability to run a campaign, debate important political issues, and most of all vote for the candidate they thought would best serve their needs.

The newspapers covered the mock election held at Vassar. This brought the students at Vassar themselves into the political realm. These women were able to prove to the public, that they had not only been educated in politics, but could participate, by running a serious campaign.

Newspaper Quotes

Judging from the various pictures of presidential candidates that are posted along the corridors, the interest of the Vassar Students in the coming election is not small...There are very few free Silverites at Vassar, and such ones as there are have to stand all sorts of practical jokes many times in the week. The neighbors of one Silverite posted upon her door, the other day, pictures of the Republican candidates. When the Silverite discovered them, she tore them down disdainfully, but upon returning to her room later she found the portraits pieced together, fastened again to her door, and underneath written, "Truth crushed the earth will rise again."

--Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, Monday, October 5, 1986

A poll of the 600 students at Vassar College show that two-thirds of them sympathize with Mr. McKinley in his canvas, and presumable they are using their influence with their fathers and brothers to vote for him....The sentiments at Vassar in the past has been an index of the drift of things throughout the country. The students come from all sections of the United States, including the far West and remote points in the South, and their families represent all shades of political opinion... The Students follow the campaign as a matter of education, but what is for general interest is that the Republican meetings have been largely attended and enthusiastic, while the attendance of Silverites has been small and without enthusiasm.

--New York Times, October 20, 1896

At ten o'clock the gong, which usually brings quiet and repose, sounded, but was answered by wild shrieks. The first returns had come! The athletes were the first on the scene, vaulting bannisters, sliding down elevator ropes. A seething mass of fair humanity soon surrounded the bulletin board. As each return came in fireworks were sent off in the corridors, at imminent risk of life and limb. And yet this is the domestic sex!

--newspaper quoted in 1897 Vassarion

At Vassar College there was a curious procession last Saturday. The girls in favor of the election of Major McKinley, who formed a large majority of the students, appeared in a bicycle parade. They carried appropriate decorations, and were reviewed and cheered by the faculty and friends. On Friday evening there will be a joint debate on the financial issue between Miss Shauffer, of Rochester, and Miss Ellery, of Cleveland, for gold, and Miss James, of Kansas City, and Miss Dudley, of Pleasureville, Ky., for silver. On election day ballot-boxes will be arranged with the formalities observed at all polling-places, and the girls will vote for their preferred candidates.

Think of the advance from the time when no woman suffrage speech might even be whispered at Vassar College!

--Woman's Journal, October 31, 1896

"My dear, there is nothing radically wrong in your sitting up in your room the night of the election to hear the returns, but if should get into the papers, think of the notoriety."

--from The Vassarion, 1897

VASSAR SOURCES

Adelaide Claftin (class of 1897), letters, scrapbooks, and diary V.C. Student Materials Collection, Special Collections, Vassar College

The Vassar Miscellany, Vassar College newspaper, November 1896, Vol. 26 No. 4

The Vassarion, Vassar College yearbook, 1897

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, Alma Mater (New York: Knopf, 1984)